“A refugee is someone who survived and who can create the future.”

Amela Koluder

The statistics seem daunting. According to a report published by the UNHCR in December 2022, 7.8 million Ukrainians have fled to European host countries in the first ten months since the launch of the Russian assault on Ukraine on 24 February. Approximately 4.86 million Ukrainians (almost 11 % of Ukraine’s population) are registered for Temporary Protection or similar national protection schemes in various European countries. This influx of refugees is far bigger than the ones (fig.1) previously experienced by European countries. As a result, they may have found themselves underprepared in the face of this wave.

Fig. 1: The asylum and first-time asylum applicants in 2014-2021 and Ukrainians registered for Temporary Protection in February - December 2022 in Europe (thousand people)

Moreover, the data also demonstrates a consistent upward trend in the number of people fleeing Ukraine every day. For this reason, it is understandable that there may be some anxiety among policy-makers about absorbing such large numbers of people into the fold of Europe’s economic infrastructure.

The potential economic burden of Ukrainian migration on European countries

In the popular political discourse of the past decade or so, refugees have come to be seen as burdens on Europe’s economic infrastructure rather than assets for growth. Migration processes as a result of military conflicts are considered synonymous with increased tax expenditures and unemployment. Some of these views are not completely unfounded – migration leads to higher public investment, at least in the beginning. For example, according to a study in Germany, only 17 percent of all refugees of working age who had arrived between 2014-17 had acquired a job after two years of staying in the country. After five years, this number had risen to 50 percent. Those employment rates were considerably lower for women (often because of family and child care obligations).

In terms of financial costs, the previous wave of refugee influx between 2015-2016 is estimated to have incurred administrative costs (such as processing and welfare costs) of around EUR 10,000 per asylum application (according to the OECD), and up to EUR 12,500 by national studies in Germany. These numbers vary across different countries as each offers a different level of support to asylum seekers. Based on such experiences, the Ukrainian refugee wave might be perceived as another significant cost for the EU to shoulder. These costs are difficult to predict due to the uncertainty regarding the total number of refugees; the length of time they might stay; and the amount the EU will choose to spend per refugee. Assuming an expenditure of 10,000 Euro per person, we can estimate that if the 4.8 million Ukrainian refugees registered for protection do not find paid work, the EU would be looking at a bill worth almost 0.3% of its GDP (17.09 trillion US Dollars in 2021). This number would be much higher in the major host economies.

That’s in theory, though. The reality might play out differently than what is being forecasted. In order to demonstrate that, I would like to focus on a few points concerning the Ukrainian influx that I believe are important. These points include a short analysis of the total number of displaced persons in European destination countries; the demographic share of Ukrainian refugees in these countries and the first signs pointing towards the integration of Ukrainian refugees into the broader European labour market.

Displaced Ukrainians in Europe: data and some unpredictable examples

It should be noted that, formally, Ukrainians fleeing Russian aggression are treated in Europe as refugees. However, from a legal point of view, they are displaced persons who have temporary protection in the EU. In contrast with refugee status, the temporary protection is valid for a certain period of time (at the current moment until 24 March 2024), after which refugees must return to their country of origin. Rights under the temporary protection scheme include a residence permit, access to the labour market and housing, medical assistance, and access to education for children. Moreover, Ukrainians are allowed to change their country of living.

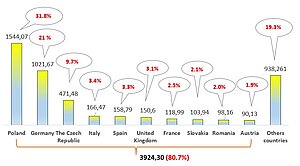

According to official information, nowadays Ukrainian refugees are almost in all European countries but their direction of movement is significantly different from each other. Moreover, refugees have separate preferences for destination countries. As of December 2022, the majority of refugees in Europe are being hosted by ten countries that include: Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, France, Slovakia, Romania, Austria[1]. The above-mentioned countries host more than 80 % of all displaced Ukrainians in Europe with particularly large shares in Poland (31.8%), Germany (21.01%) and the Czech Republic (9.7%) (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: The number (thousand people) and distribution (%) of Ukrainian refugees in Europe in December 2022

It should be noted that, for refugees, Poland and the Czech Republic are often the first choice of destination due to their cultural and geographical proximity to Ukraine, as well as family and friends that many refugees have in these countries. However, the data shows that after first crossing into neighbouring countries, most refugees move on to wealthier EU member states.

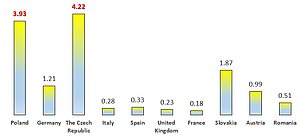

The statistics show that Ukrainian migration has been rapidly changing the demographic structure of some countries. If we take into account the number of refugees relative to the total population, then the Czech Republic and Poland have seen the biggest demographic changes since December, with Ukrainians now making up 4.22% and 3.93% of the total population respectively (fig 2).

Fig. 3.: The share of Ukrainian refugees out of the population (%)

Yet rather than being an economic burden, Ukrainians in these countries, which are not the wealthiest in Europe, appear to be doing well on the labour market. According to the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs of Poland, 430,000 Ukrainian refugees had found employment since the beginning of the war. This means that about two-thirds of the total refugees of working age (670,000) have a job. Similarly, as of August, the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy of the Czech Republic reported that more than 101,000 Ukrainian refugees had found work there and, moreover, this was mostly long-term work. At the same time, the main problem of refugees' employment in both countries is work below their qualifications. Unfortunately, official data does not allow us to fully describe the process of Ukrainian refugee integration in other European countries at the current moment of time. But examples from the Czech Republic and Poland offer us a glimpse into the potentially positive impact of Ukrainian migration to European countries. The economist Giovanni Peri argues that refugees from Ukraine may be a human capital windfall for receiving countries like Poland, Romania, Moldova, and Hungary. Experts from the migration platform EWL predict that in the future, European countries may vie to take in more Ukrainian refugees in order to solve their problems of labour shortages. Overall, Ukrainian refugees are expected to increase the EU workforce between 0.2% and 0.8% in the medium term.

Potential impacts of Ukrainian refugees on European countries

To my mind, it is difficult to predict how the influx of refugees will impact Europe’s economy just yet. There are still a lot of unpredictable variables to take into account: for example, whether this will be a long and protracted war or if a resolution will be reached soon. This will decide whether Ukrainians can come back to their country soon or not. The longer they stay in other countries, the less likely they are to return.

This presents two scenarios: In the short-medium term, the influx of Ukrainian might lead to an economic pressure on receiving countries as refugees try to gain knowledge of local languages and find work. Whereas, in the long-run, Ukrainian migration can be a solution for some of Europe’s economic woes and troubles – namely, lack of young skilled labour as more people enter retirement and become dependent on state-provided pensions, healthcare, and so forth.

Echoing the opinions of experts recently interviewed by Voice of America (VOA), I would argue that quickly removing barriers to employment (as the Polish authorities have done) and mobilizing Ukrainian diaspora to help with the adjustment and labour engagement of the newly arrived compatriots would go a long way in helping Ukrainian refugees to capitalize on their mostly high professional qualifications and enter the labour market faster. Obviously, the positive signs emanating from the Polish case are not a given, nevertheless, implementing policies that utilize the distinct feature of Ukrainian migration – a bigger share of highly skilled people – could lead to a win-win situation for both the refugees and the hosting countries.

Dr. Oksana Denys is a Ukraine Fellow at the Research Center for the History of Transformations (RECET) at the University of Vienna. She is currently working on a project entitled “Impacts of Ukrainian Refugees on the Social and Economic Life of Austria”. Previously, she worked as a Professor at the Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute and International University of Finance. Oksana was a member of the working group of several international projects supported by the Global Compact UN in Ukraine, International Finance Corporation, and others.

Cover photo by Pakking Leung via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-4.0

[1]I take into account the countries for which we have available data concerning: 1) refugees recorded in countries; 2) refugees having temporary protection; 3) refugees crossing borders.