On 20 October 2020, President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić laid wreaths at the Monument to the Unknown Hero on the mountain of Avala near Belgrade, the memorial built in the Kingdom in Yugoslavia in 1938 that commemorates the Serbian soldiers fallen in the First World War. Vučić left a note in the memorial book, honouring “the immortal liberators” whom the Serbian president thanked for their courage and great sacrifice. “Heroes, eternal glory and gratitude to you for freedom”, he wrote, emphasising that Belgrade and Serbia today show that their sacrifice was not in vain.

Although this mnemonic act took place at one of the most prominent First World War sites of memory in Serbia, it was actually about the Second World War. Namely, 20 October is the Day of Liberation of Belgrade, the day that celebrates the 1944 liberation of the capital city by the joint efforts of the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Movement and the Soviet Red Army. As much as this act was widely ridiculed, the Serbian president – accompanied by the Minister of Defence and the Chief of General Staff of the Serbian Armed Forces – was not the first among Serbia’s political elites who might seem to have mixed up their world wars. The intertwinement of the memory of the two world wars was also characteristic for the representatives of the Democratic Party, the political predecessors of the Serbian Progressive Party which is now in power. It was also the case during the early period of socialist Yugoslavia.

In the memory culture of socialist Yugoslavia, the uprising and liberation in the Second World War were embedded in the long history of people’s struggles and uprisings. In Serbia during this period, it was common for the speeches given at People’s Liberation War commemorations to include references to the anti-Ottoman Serbian uprisings and other events from Serbian history. The regime appropriated the First World War memory as well. In the early 1950s, the commemoration of the Day of Liberation of Belgrade took place at the First World War memorial on Avala, before the memorial cemetery of Belgrade liberators was built.

Today’s amalgamation of the memory of the First and the Second World Wars in Serbia is different and has to do both with the relationship of the post-Milošević political elites to Yugoslav state socialism and with the recent rise of right-wing populism. While laying wreaths at a memorial to First World War soldiers, Aleksandar Vučić did not mention who the immortal liberators were and what their victory against fascism meant. The Partisans were an all-Yugoslav movement led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, and their struggle against the Axis occupation and its collaborators was a simultaneous socialist revolution. This is invisible in commemorations of their victory.

In her recent book, Jelena Subotić talks about the process of Holocaust memory becoming a proxy for remembering communism in Eastern Europe and terms it memory appropriation. The appropriation and inversion of Holocaust memory exists in Serbian memory politics, too. Additionally, during the last decade, the communist-led and victorious People’s Liberation War has been appropriated for various inward- and outward-oriented needs of Serbia’s political elites. At the same time, the Second World War is a proxy for remembering the First World War and other wars throughout Serbian history officially referred to as the liberation wars of Serbia (oslobodilački ratovi Srbije). The armed conflicts that followed the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the 1990s are also counted among the liberation wars.

Belgrade Liberation Day was not always remembered. In the hegemonic anti-communist political climate of the immediate post-Milošević period, the official politics of memory rather aimed at criminalising the Partisans while rehabilitating their enemies – the Axis collaborators who were on the defeated side of the Second World War. In the search for a role model from the Second World War politically more appropriate for the post-socialist nation-state than the Partisans, political actors construed the Chetniks as the national antifascist movement and as victims of communism, because of the post-war retribution they faced when their leader Dragoljub Mihailović was sentenced to death and executed in 1946. In Belgrade, the Partisans and Red Army commanders were erased from street names while the Cemetery of Belgrade Liberators was left to ruin.

A sudden change came in 2009, when the Liberation Day celebration was organised under the title “Belgrade Remembers”, after almost a decade of forgetting. It coincided with the state visit of Dmitri Medvedev, at the time President of Russia. Serbian state officials, including President Boris Tadić, managed to go through the series of commemorative activities and speeches without mentioning the Partisans, Josip Broz ‘Tito’ or socialist Yugoslavia. What followed in 2014, when the Serbian Progressive Party was already in power, was a pompous military parade, organised four days before the actual Liberation Day so that Vladimir Putin could attend it. In this period, the First World War song “March to the Drina” established itself as an inseparable part of the celebrations of Liberation Day and Victory Day on 9 May. The Army of Serbia became the key memory actor in commemorations of the People’s Liberation War, as their purpose became celebrating the Serbian army in past and present. This is also why the government uses the occasion of Liberation Day to organise spectacular displays of its military power.

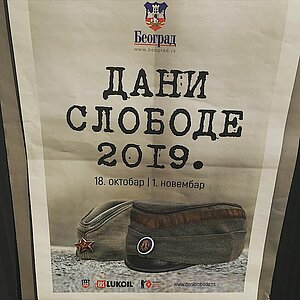

In addition to the commemorative military parade in 2014, the first in Belgrade since 1985, the official merging of the two world wars was confirmed through the invention of the Days of Freedom (Dani slobode), a two-week-long joint commemoration of the liberation of Belgrade in both the First and Second World Wars. It takes place between 20 October and 1 November, connecting the two liberation days and involving a series of activities such as a street race, concerts, historical re-enactments, a memorial procession, displays of Serbian military power, and the now traditional concert of the Alexandrov Ensemble from Russia. For most primary school pupils across Belgrade, 20 October starts with a mandatory class about the battles for the liberation of the city in 1944.

The concert of the official choir of the Russian armed forces is not a random part of the liberation festivities. The return to commemorating the People’s Liberation War has gone hand in hand with the strengthening of relations between Serbia and Russia. Russian state representatives and diplomats are crucial actors of the memory politics on the Second World War in Serbia. This “memory alliance” is most visible on the occasions of Victory Day and Liberation Day that honour and historicise the Serbian-Russian friendship. Russian memory politics is also a source of inspiration for Serbian memory actors, with the appropriation not only of generic commemorative practices such as military parades to the Serbian context, but also of very particular acts and symbols, such as the Immortal Regiment and St George’s Ribbons.

The Days of Freedom as a state-sponsored project of world wars’ fusion illuminate the memory appropriation, historical revisionism and relativization of historical events that are at the core of Serbia’s official memory politics. “The ideologies pass, as concerts, exhibitions and theatre plays will show, while the desire for freedom is eternal”, says Aleksandar Gatalica, author and art director of the 2019 Days of Freedom, talking about the symbols of King Peter I and hammer and sickle on the soldiers’ caps as no longer conflicted but reconciled. The national reconciliation discourse erases the specificities of historical contexts, their consequences and legacies as well as ideologies, merging all actors under the symbolic umbrella of the Serbian army. The construction of a glorious military past as a source of pride is, however, not unique to Serbia’s post-socialist transformation processes – or to contemporary Russia – but exemplifies the wider phenomenon of the interplay of right-wing populism and memory politics. Hybrid memory politics of authoritarian democracies blend nationalism and a vision of the past through the binary lens of heroism and victimhood with “a populist self-representation as the historical underdog”. The mnemonic efforts of contemporary populists resemble the traditional nation-building processes that aimed at constructing a coherent national history, usually in combination with military pride. At the same time, they are also a novel phenomenon influenced by the current rise of populism and emergence of new forms of authoritarian democracies at the global level and the templates and tropes of memory that have developed since the end of the Second World War.

Jelena Đureinović is Scientific Coordinator of the research platform "Transformations and Eastern Europe" at the University of Vienna. She holds a PhD in History from Justus Liebig University in Gießen. Her main research interests include memory studies, nationalism studies, postsocialism, history of Yugoslavia and the post-Yugoslav space. Her book The Politics of Memory of the Second World War in Contemporary Serbia: Collaboration, Resistance and Retribution was published with Routledge in 2019.