I stood before the Saint Anne’s Gate ready to enter the Vatican City. It was January 2023, particularly wet and cold. I had just crossed Saint Peter’s Square, rather empty in the brisk winter weather, cobblestones gleaming from the morning rain. I had been waiting for this moment for nearly three years. Yet, there are scholars who waited decades. The part of the Vatican Apostolic Archive pertaining to the period 1939-1958 opened in March 2020 and, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, closed just a couple of days later.

Figure 1 Saint Peter’s Square in January 2023.

I first learned about the opening of the archive in 2019. Back then I was working on refugee letters and appeals as a part of the Reckoning with Refugeedom project team at the University of Manchester. I focused on the writing of people displaced as a result of World War II. As I was looking at a letter penned by a refugee from a forgotten-by-all refugee camp in British East Africa to Winston Churchill, I thought it was a safe bet to assume that refugees wrote also directly to the Pope. Were such letters preserved though? If so, how and where? And what about the wider context of the Church’s aid to refugees in this period?

I came across records on the Catholic initiatives on behalf of the displaced in the archives of UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) and IRO (International Refugee Organization), as well as the records of the Polish embassy to the Holy See, preserved in the documentation of the Polish government-in-exile in London. Yet, only now the documents on that period originating from the Holy See, the central government of the Catholic Church, were to become accessible.

I consulted it with my mentor, gathered the necessary documents and submitted an application to be granted access. Yet, my first trip took place only three years later. The permission to enter the archives can be granted to qualified scholars conducting scientific studies. You can consult the rules of access on the archive’s website. I prepared my application: I uploaded copies of my PhD diploma, passport, presentation letter, and photograph.

I was very excited when I managed to book a place in the reading room. Because of high demand and limited space, it must be reserved months in advance. My excitement dwindled soon as I learnt that my university would not approve any research trips abroad as the new wave of Covid swept through the UK. Before I could think about the next visit, my project of then finished and so did my potential funding. For some time, I abandoned the idea and came back to it only when applying for a fellowship at the Central European University. Finally, I flew to Rome, left my suitcase (packed to the brim for a one-month stay) in a small guesthouse a short walk from the Vatican, and made my way through Roman streets toward the great cupola towering over the city.

The Vatican Apostolic Archive (or VAA for short, in Italian: Archivio Apostolico Vaticano) is located in the Vatican City and serves as the central archives of the Holy See. Until 2019, it was named Archivio Segreto Vaticano or Vatican Secret Archive. Nested in the walls of the Cortile del Belvedere, it houses over six hundred fonds including historical archives from various sources. These sources range from offices of the Curia and papal diplomatic representations to archives of families, individuals, councils, religious institutes, and miscellaneous collections, spanning centuries of documentation significant to the Vatican's history.

The archives serve to preserve and provide access to documents integral to understanding the Vatican's past and its global engagements. Now, documents up to the end of the Papacy of Pius XII (9th October 1958) can be consulted (with some exceptions). What interests me is precisely this last part, in particular documents from the last phase of World War II and the early Cold War.

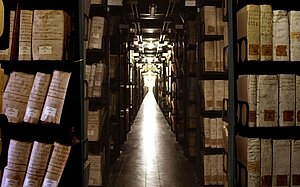

Figure 2 Hallway in the Vatican Secret Archives around 2012. Source: Abaca Press/Alamy.

I passed the gate, checked in with the Swiss Guard, and got my entry pass. I walked through Cortile del Belvedere, passing the Vatican Library. As I was sitting on a carved wooden chair in front of a big portrait of Pope Francis, I didn’t know what to expect, as each archive differs in ambiance, ranging from very impersonal to more cozy and informal settings. Luckily, the reception was very cordial, and made me feel welcome and encouraged.

The first thing I noticed after having taken the elevator to the third floor was that when I looked out of the window, the gardens were at eye level. It evoked the verticality of the Vatican's architecture, tightly clustered within less than half a square kilometre, while also boasting extensive underground structures. The archive is mostly underground, housed in a fireproof two-story reinforced concrete bunker. It has an impressive expanse of 85 kilometres of shelving.

While I prepared as much as I could in advance, only once in the archives I could consult indexes. Those are available in the Leon XIII Index Room, „the gateway all researchers pass through”, as the official description of the archives has it. Indexes are stuck on shelves reaching to the ceiling. I decided what materials to consult first, filled out a form on one of the computers and went to the adjoining Pio XI Reading Room to wait until the archivists brought requested boxes to the counter. The archive has sixty places for researchers in the reading room, and typically all desks are taken.

As I delved into the documents, unable to take photos due to restrictions, I began transcribing, along other researchers. The room echoed with the tapping of keyboards on laptops mixed with the soft scratch of pencils against paper. I started my research by consulting the documents filed under Pontificia Opera di Assistenza and Commissione Soccorsi. And indeed, as expected, refugees did write to the Pope, and abundantly so. That meant that I had in front of my eyes a vast material for writing the social and cultural history of the postwar and the early Cold War.

While the archives are multilingual, the majority of the documents for the period of WWII's aftermath is in Italian. Still, letters reaching the Vatican were penned in various languages – Polish, German, Russian, French, Spanish, Latin, even Esperanto. You can read more on the documents of the Holy See on refugee aid and my initial findings in the chapter “The Vatican’s Aid to Displaced Persons and Refugees in the Aftermath of World War II”.

Slowly getting tired, I lifted my head from the files and peered out at an internal courtyard with a fountain (though it was dry!) and some charming plants. It is called Cortile della Biblioteca, as it also has a direct entrance to the Vatican Library. I ventured for a stroll to take a closer look at the plants but then discovered a quaint bar (without a signboard, the only indication being a couple of then-empty chairs and little tables nearby). It quickly became my go-to spot for an early afternoon snack and coffee (never ever a cappuccino after 11am, as I learnt the hard way). I made my way back to the reading room. Since that first visit, I spent long hours there, and Rome became a fixed point on my professional and personal map.

I hope to share with you more about my research process and my findings soon. You can check out the list of my upcoming talks here.

Figure 3 Angels Unawares, a bronze sculpture depicting migrants and refugees from various historical era by Timothy Schmalz in St. Peter's Square in the Vatican. January 2023. Fot. Katarzyna Nowak.

Katarzyna Nowak is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Postdoctoral Fellow at RECET. Her book Kingdom of Barracks. Polish Displaced Persons in Allied-Occupied Germany and Austria was published by McGill-Queen's University Press in 2023. Her current project is entitled “Knocking on the Vatican’s Gates. Refugees, the Holy See, and the Spectre of Communism, 1945-1958.”

This article was first published on her research blog.