This piece is part of a series of articles related to the war in Ukraine. The longer version of this text was originally published by Zeitgeschichte online.

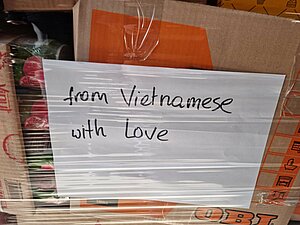

One of the boxes with food products organized by the Vietnamese minority in Poland, Feb. 2022, courtesy of Phan Châu Thành.

As much as war is about armed military conflict, it is also fundamentally about mass displacement, broken lives, and lost futures. This simple truth has become way too obvious in large parts of Poland, where providing food, clothes and shelter to strangers, and collecting donations to help refugees from neighboring Ukraine have become common practices among “ordinary” people. With over three million (as of March 16) Ukrainians fleeing war, Poland became a hub for more than half of them, often as a first stop on route to their families and friends across Europe. Much of the efforts of this grassroots mass mobilization to help those escaping their war-torn country falls on the shoulders of various parts of society, including individual activists and non-activists as well as civil society organizations.

Initiatives of the Minority Communities

What is perhaps less visible in this civil society mobilization and its media coverage are the efforts of migrant and minority communities that do their share in offering relief to those fleeing from Ukraine. For instance, members of the Vietnamese community, one of the oldest and largest non-European communities in Poland whose roots go back to the 1950s, organized a food tent at the remote border crossing station in Zosin-Uściłóg. Launched by first- and second-generation migrants from Vietnam, the initiative also involved collecting money and providing daily necessities as well as housing in the Vietnamese Pagoda and the Asian wholesale trade center in Wólka Kosowska. On March 10, Ngô Văn Tưởng, who had come to Poland as a student before 1989, launched the informal initiative “Gorące obiady” (hot lunches) that involved Vietnamese restaurants delivering around 60 warm lunches daily to refugees. This form of social activation builds on the experience of Vietnamese activists during the pandemic when immigrant-owned restaurants began delivering free meals to medical staff battling the pandemic in Warsaw and beyond.

As carriers of the “invisible wounds” caused by war and decolonization, the Vietnamese know all too well the brutalizing dynamic and psychological impact of a seemingly endless armed conflict. The older generations of migrants from Vietnam also personally know many Ukrainians with whom they shared the ebb and flow of the 1990s as migrant workers running small restaurants and working at outdoors markets. As their example shows, the experience of bloody decolonization can map onto that of the regime transition in Eastern Europe. It is precisely this blending of perceived war-time commonalities, shared first-hand experiences of turbulent post-socialism, and the concrete skillsets of first-generation urban migrants working in the food industry and transnational trade business that propels the Vietnamese community in Poland to help refugees from Ukraine today.

Another example of grassroots activism comes from the African-Polish community that has become active in supporting Black people and people of African descent fleeing Ukraine. A central role in this movement of support is played by an alliance of organizations, whose activists provide free rides from the border, access to temporary accommodation, legal services, counselling, and general assistance for those willing to settle in Poland. This initiative is as much about reacting to the atrocities of war as it is about countering the disparities in treatment of various groups of refugees at the Polish-Ukrainian border, and the violence some of them suffered in Poland at the hands of right-wing hooligans. Against this backdrop, it quickly became clear that pre-existing infrastructures and local networks of activists with an experience in fighting for the fair treatment of Black and Brown people in Poland were able to respond to an emerging need arising from the specific wartime hardships faced by groups that are racialized and othered.

The Polish Roma community has been assisting Ukrainian Roma people who, at times, also faced racist treatment while evacuating from Ukraine. A scholar and activist, Joanna Talewicz not only helps Ukrainian and Ukrainian Roma refugees but also fights anti-Roma biases in the media coverage of the war. Talewicz is a co-founder of Fundacja w stronę dialogu (Foundation for Dialog) that is collecting donations for fleeing Roma people and provides all types of support similar to the ones offered by other NGOs and activist circles. One of the major challenges the foundation addresses is the prevailing and deeply rooted racialized stereotype of Roma people that presents them as criminal and lazy. These powerful and harmful representations of Roma people often make it harder for them to find housing and transportation. Like African-Polish activists, Polish Roma activists point to the fact that the wartime experience of Roma people and other racialized communities fleeing Ukraine is layered with biases. In that sense, their experience of wartime violence and forced displacement has an intersectional dimension to it. (Without doubt, Ukrainian women and children seeking refuge also experience forms of intersectional violence that disproportionately impact women such as trafficking, rape, and other challenges related to gender that are often overlooked). Activists helping Roma refugees feel less supported as they, unlike Vietnamese and African-Polish activists, have no embassy and few institutions to turn to for help.

The Underbelly of Help

Despite the massive outpouring of self-organized support for refugees from Ukraine, several major challenges are looming large over this mobilization. How long can such grassroots forms of help that build on collective acts of kindness and solidarity last? With more and more volunteers facing the enduring stress of working in a logistic chaos and shrinking resources there seems to be growing unease about the limited involvement of state institutions and the lack of a sustainable and systemic response. Some activists who have been active at the Polish-Belarussian border to address the desperate situation of asylum-seekers for the last months express frustration with the wide gulf between the treatment of refugees there and those coming from Ukraine. Just a few hundred kilometers north of the Polish-Ukrainian border, refugees were and still are being pushed back onto the Belarussian side by the Polish Border Guard and experience violence (including sexual violence) from the Belarussian Border Guard. Families with children were and still are freezing in the woods, not knowing if and when they will be able to safely cross into Poland.

Broadening the Scope of Care and Aid

Everyone would probably agree that instead of pitting one group against the other, comparing their levels of suffering, and their raisons d'être, it is important to ask: Who counts as a refugee and which refugees count? Although answering such a seemingly innocuous question might be painful, we need to ask it in order to prevent reproducing exclusions and marginalizations in the very act of solidarity and helping. To inquire whether racist hierarchies or a sense of cultural proximity might play a role in shaping and limiting aid and solidarity touches on a thorny and difficult topic, but instead of hindering spontaneous and conscious support for those in need it should broaden its scope. There is little doubt that years and years of anti-refugee discourse propagated by the conservative part of the Polish authorities have tapped into, as well as amplified, racial sentiments. The effects are now becoming visible even within this enormous and impressive wave of solidarity.

At the same time, racism might not be the sole factor in explaining divergent reactions. Many commentators from “the West” forget or do not fully realize that the cultural and geographical proximity of Poland and Ukraine is woven deeply into a difficult but intimate shared past. This historically rooted and culturally encoded closeness magnifies a sense of collective responsibility for Ukrainian society that has become a victim of an imperial state perceived as a common enemy, as it has posed an existential and real threat to Poland as well. Against this background, the violence targeting Ukraine is opening up old wounds while creating new ones. In that sense, the mass support for Ukrainian refugees in Poland cannot be simply boiled down to arbitrary favoritism. Although collective burnout, limited resources, and the uneven redistribution of help provide the dark underbelly of the current, and impressive mass mobilization across Poland, the point is not to erase the tremendous support offered by Polish society and its humanitarian as well as political value. Rather, the point is to realize that even grassroots initiatives with the best intentions can go hand in hand with forms of disparate treatment and exclusion that are as deeply rooted as the sense of connection and commitment that underlies the mobilization.

The support coming from the migrant and minority communities build on semi-organized practices of solidarity and help that are often rooted in prior experiences, activities, and discourses. African-Polish and Roma activists do not merely offer an ad hoc support for refugees—they also continue to battle discrimination and systemic challenges. The Vietnamese do not only focus on providing food to refugees—they appropriate and turn around the stereotypes and roles in which they are pigeonholed.

Ultimately, those in need of support are civilians trying to flee under circumstances that are hard or even impossible to imagine for most of us. As Viet Thanh Nguyen, himself a former refugee, once wrote: “To become a refugee is to know, inevitably, that the past is not only marked by the passage of time, but by loss—the loss of loved ones, of countries, of identities, of selves.”[1] It is also this knowledge of loss and remarkable agency that motivates many to help those who are at risk of losing everything today.

Dr. Thuc Linh Nguyen Vu is a postdoctoral fellow at the Research Center of the History of Transformations (RECET) at the University of Vienna. She is currently working on a book manuscript entitled Practices of Togetherness: Jacek Kuroń, Pedagogy, Communities of Care, and Political Opposition in Poland (1955-1982). Her second book project is on the socialist entanglements between Poland and Vietnam after 1955. Nguyen Vu is interested in the history of Poland, Vietnam, cultural history, decolonization, and global Cold War. She has published in scholarly (Cahiers du Monde Russe, History Workshop Journal, etc.) and non-scholarly (TAZ, Zeitgeschichte-online, Krytyka Polityczna, etc.) outlets.

***

If you wish to support refugees in Poland, consider donating here:

https://fundrazr.com/africansinukraine?ref=ab_94qB6b842It94qB6b842It

[1]Viet Thanh Nguyen, et al. The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives (New York: Abrams Press, 2018), 22.